Once Upon a Time in the Turkish Cinematheque Association (1965-1980)

Turkish Cinematheque Association was a cinema center active between 1965 and 1980, particularly bustling until 1975. The decade between 1965 and 1975 constituted the most fruitful years of the association. In fact, it was just as fruitful for the entire cultural sphere namely the theatre, music and literature in Turkey. During these years, artistic activities were well adopted by different segments of the society and became a more visible part of the urban life. This was also the case for cinema and the Cinematheque Association. The Turkish Cinematheque can be viewed as a social and cultural environment bearing the characteristics that could only emerge under the circumstances of that specific period.

The Cinematheque Association reflects the debates, problems, contradictions, aspirations, financial difficulties, technical impossibilities, and amateur spirit of the period, the desire to remain independent from every power group and authority while it comes to the fore as one of the institutions that shaped and marked the period in question. The association embodied (and from time to time defied) almost all major dynamics of intellectual groups who adopted dissident political opinions as well as the dynamics of non-profit cultural organizations with an amateur spirit, who cared about social issues and bringing exquisite films of the universal culture to Turkey hence left their mark on the period.

In the 1960’s, cinema had been undergoing a rapid change all over the world and Turkish cinema was by no means exempt from this process of transformation. The way Yeşilçam cinema operated, the movies it produced were all disapproved by the film critics gathered around the Cinematheque Association, who criticized Yeşilçam for being under the influence of capital as well as American imperialism, in line with economic interests. For instance Onat Kutlar, in an article he penned in 1967, criticized the existing cinema and made suggestions concerning how to establish an alternative cinema:

“…the paths are closed to those filmmakers who don’t want to succumb to conformism, who wish to bring in their perspectives, a new expression, a new form to a brand new world. Firstly, it all starts by totally submitting to the market’s patterns and then, these patterns are a little stretched at the expense of big compromises. So a nonconformist filmmaker is obliged to pursue opportunities outside the market. Latest technical and aesthetic developments enable to make films inexpensively. These new cinema generations could thus find art-lover capital owners to make pioneer films, even realize their dreams to shoot short films with their own money. These attempts would initially remain as individual ventures hence perhaps fail to represent local cinema. On the other hand, if they make substantial films and not fall into the trap of emulation in the name of art, they will benefit from the international opportunities of cinema and more importantly contribute to the formation of a ‘quality market’ in the country with the support of the Cinematheque, cinema clubs and the press. There’s no more problems once this market emerges because mainstream producers who consider this area profitable would enable making such films even if only for the sake of profit.”

Onat Kutlar suggested short films in order to transform the movie industry, pointing out that independent and revolutionary cinema can be achieved through low budget short films. He said that “the short films are the Molotov cocktails of cinema”. The editorials published in the Association’s house organ Yeni Sinema suggested not only shooting films but also that the Association screens examples of world cinema –European art house films and the cinema of socialist countries in particular. It was necessary to screen these films to help raise generations that would approach cinema differently whereas the chance of seeing them was very limited until then. It was also suggested that presenting theoretical literature to the readers through Yeni Sinema is crucial in terms of raising awareness on the intellectual quality of cinema.

First of all, we have to say that the founders of the Cinematheque Association, who came up with this project were all esteemed intellectuals like Onat Kutlar, Şakir Eczacıbaşı, Hüseyin Baş, Aziz Albek, Semih Tuğrul, Tunç Yalman, Tuncan Okan, Sabahattin Eyüboğlu, Cevat Çapan, Macit Gökberk, Nijat Özön and Muhsin Ertuğrul...

First of all, we have to say that the founders of the Cinematheque Association, who came up with this project were all esteemed intellectuals like Onat Kutlar, Şakir Eczacıbaşı, Hüseyin Baş, Aziz Albek, Semih Tuğrul, Tunç Yalman, Tuncan Okan, Sabahattin Eyüboğlu, Cevat Çapan, Macit Gökberk, Nijat Özön and Muhsin Ertuğrul... The Association which thrives as a common ground for intellectuals of all ages at the beginning, ends up being dominated by the revolutionary students of the period in the following years and especially after 1968 the “decent environment” rapidly dissolves. The fact that the Association was a center of attraction for the youth since its foundation manifests itself in the example of Jak Şalom who became a member of the association at a young age, later worked in the association and remained a “Cinematheque person” for the following years.

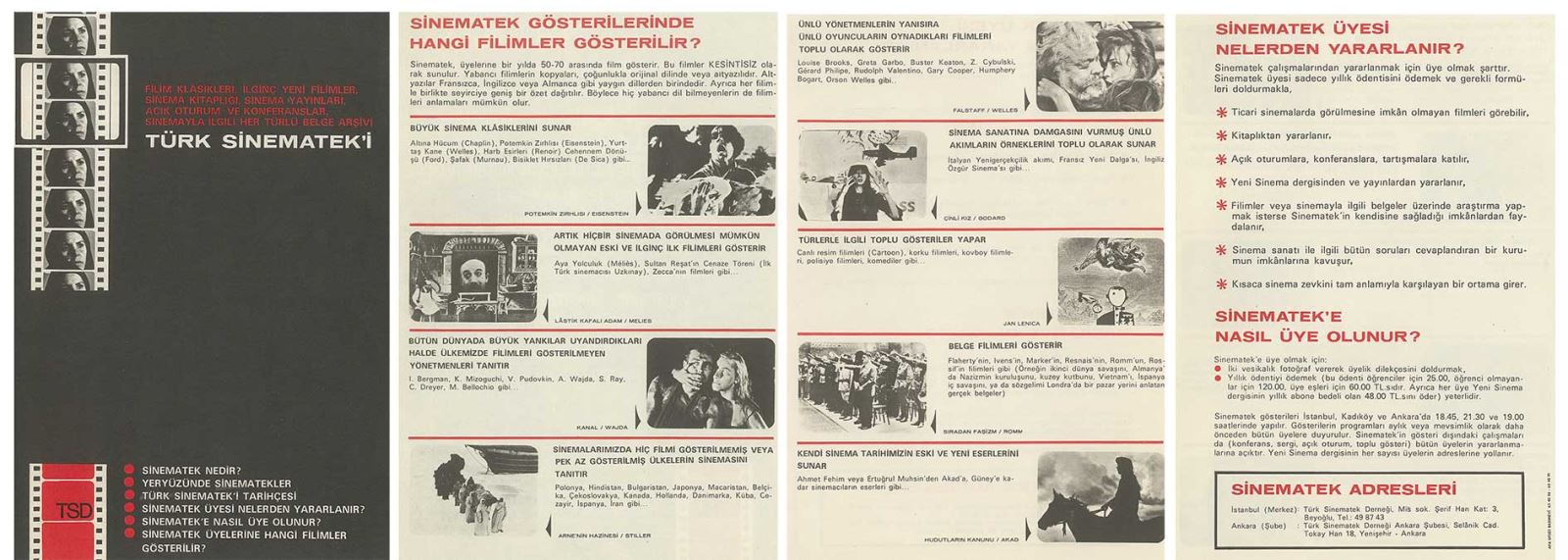

The Cinematheque Association set off with a pretty rich program including examples of “auteur” cinema in particular. The extensive program had films of directors like Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut from the French New Wave; Luchino Visconti and Vittorio De Sica from the Italian Neorealism as well as prominent filmmakers from the American cinema, Eastern European countries and the Soviet Union (especially Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov from the Soviet Montage Cinema).

It should be noted that films from the countries to the east of the “iron curtain” and programs from the French Cinematheque constituted a significant part of the screenings. Having discussions about the films after screenings and talks about the need to have an alternative cinematic understanding in Turkey took the film viewing experience to a more intellectual level. Şakir Eczacıbaşı likened the Cinematheque’s role in the development of cinema to the role of libraries in the development of literature. The fact that the Cinematheque Association also put emphasis on cinema publications is one of the factors that enabled it to take on that role. The house organ of the Association, Yeni Sinema introduced to its readers many alternative film movements and directors from the French New Wave and Italian Neorealism to Cinema Nôvo from Brazil. Onat Kutlar relates their motivations at the time as follows:

Establishment of the Cinematheque was very exciting for us all. The cultural values of Turkey, their cinematographic meaning on one hand and our passion for cinema on the other... We were unable to see our favorite films’ directors in our own country. It was us who wanted to watch films in the first place.

As Onat Kutlar highlights, the Association enthusiastically continues with an increasing number of screenings: “At first, it was 3 films a week. Slowly, it went up to 20 films a week in our seventh year. How many films we screened in a year, you do the math…” The Association met with state oppression through censorship as soon as it started to be influential. Within the first decade during which it was particularly influential, it screened about 3000 feature films and about 2000 short films; received films from 37 countries, hosted about 100 important guests from various countries; also organized many panels, series of screenings and conferences. Published books albeit not many and the number of cinema clubs inspired by the Cinematheque reached up to 20.

Excitement, amateur spirit, sincerity, political engagement, wish to change the world, confusion, clear-headedness, depth, superficiality, fashion, conflict, contradiction, discussion… It is possible to observe these seemingly incompatible concepts in the artistic environments and entourages of the time. The Cinematheque Association served as a cultural forum in the enlightenment struggle of Turkey during 1960’s and 1970’s; contributed to the artistic and cinematic culture of our country via the films it screened and the discussions it enabled. Just as this precious organization emerged under the circumstances of its day, today’s film culture will no doubt create its own formations under the current circumstances. Bringing together the productivity of the filmmakers since 2000’s with the values of the past and a pluralist understanding of culture is the most important mission of these formations.